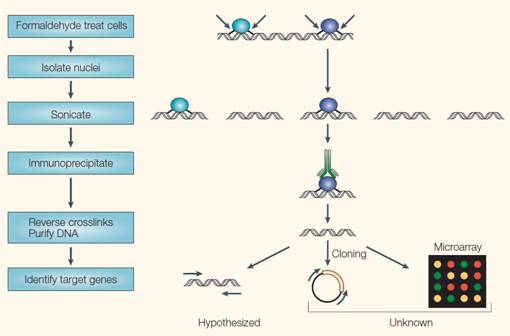

染色质免疫沉淀(ChIP)是研究蛋白质-DNA相互作用的一项强大技术,广泛用于多个领域的染色质相关蛋白的研究(如组蛋白及其异构体,转录因子等),特别适用于已知启动子序列或整个基因位点的组蛋白修饰分析研究。这项技术采用特定抗体来富集存在组蛋白修饰或者转录调控的DNA片段,通过多种下游检测技术(定量PCR,芯片,测序等)来检测此富集片段的DNA序列。

ChIP技术自诞生之后,已成功的应用于人或动物细胞和组织[1]、植物组织[2]、酵母[3]以及细菌、质粒[4]。由于在信号转导和表观遗传研究中的突出作用,ChIP在肿瘤[5-7]、神经科学[8-10]、植物发育[11-13]等领域中应用非常广泛,同时有关细胞凋亡[14]、雌激素信号转导[15]、胰岛素抵抗[16]、组织发育[1]的文献中也用到ChIP。

目前,最常见的有以下两种ChIP实验技术:

1. nChIP: 用来研究DNA及高结合力蛋白,采用微球菌核酸酶(micrococcal nuclease)消化染色质,然后进行片段富集及后续分析,适用于组蛋白及其异构体,例如[17-19];

2. xChIP:用来研究DNA及低结合力蛋白,采用甲醛或紫外线进行DNA和蛋白交联,超声波片段化染色质,然后进行片段富集及后续分析,适用于多数非组蛋白的蛋白,例如[9, 15, 20]。

ChIP试验的一般过程[21]

以上两种方法在分离DNA-蛋白质复合物之后,对DNA进行PCR扩增,验证目标序列的存在。除验证实验外,ChIP DNA也可以进行测序分析,这种方法被称为ChIP-seq[22];也可做芯片分析,这种方法被称为ChIP on CHIP或ChIP-CHIP[23]。这两种方法都可用于分析感兴趣蛋白结合的未知序列,而不需要知道目标序列的详细信息,因此可以进行探索性的研究。当需要对DNA结合的蛋白复合物(两个或两个以上蛋白共同结合在DNA上)进行研究时,可以采用reChIP技术对DNA蛋白复合物进行再次富集,从而分析两种蛋白同时结合的DNA片段,例如转录调控因子及其受体复合物[24]。

相比其他DNA与蛋白相互作用的研究工具,ChIP的突出优势在于通过检测蛋白(in vivo)与DNA的物理结合,研究体内真实情况下的染色质结构,因此得出确凿的诱导或阻碍转录的证据,这对构架信号调控网络至关重要。同时,通过此工具也可以区分转录调控的直接作用和非直接作用[21],从而使研究者对转录调控过程有更精确而深刻的认识。

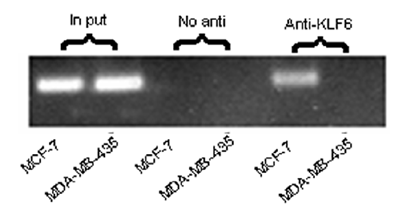

ChIP试验的结果示例[6]

基于上述的技术优势,ChIP首先被用来研究分子层面上的调控机制,区别于其他研究转录调控相关性的实验手段。这类分子机制研究多数是关注于DNA结合位点是否为启动子区或其他转录调控位点。例如,癌基因myc上游调控机制的研究非常之多,然而大多停留于假说阶段。Sotelo等人[20]于近期首先发现转录因子Tcf-4和β-catenin共同上调c-Myc基因调控因子enhance E的表达,然而luciferase reporter实验结果仅能证明β-catenin和转录因子Tcf-4与enhance E的相关性,无法提供证据表明这两种细胞因子如何作用于enhance E基因上。因此,他们采用了ChIP技术,证明前列腺癌LnCAP细胞中是Tcf-4而不是β-catenin直接结合到enhance E基因上,这就表明Tcf-4直接参与到enhance E的调控中。此结果与Hatzis等人[25]对直肠癌细胞系LS174T做的ChIP-CHIP测得的结果一致,证实了一直以来研究者关于myc存在远端增强子的猜测。类似地,有研究表明β-catenin与FGF2相互作用,影响神经干细胞增殖或分化,然而具体如何协同调控增殖或分化进程尚未知,直到Israsena等人[10]用ChIP试验证明了β-catenin仅在FGF2存在时与neurogenin启动子直接结合,从而调控FGF2下游信号通路。这就解释了FGF2在该信号通路中的主导作用。另一种常见的分子机制研究则是关注于DNA结合位点下游的基因,用此类基因的表达活化或抑制来解释表型上的差异。例如,Seo等人[26]采用ChIP技术分析了NeuroD结合位点的下游基因,发现了多个转录调控因子,因此得出结论,NeuroD则位于该神经发育调控网络的重要位置。

其次,ChIP也往往被用来验证其他DNA-蛋白质相互作用研究方法所得的结果。由于其他研究方法并非在体内(in vivo)实现或者尚不能得出确切结论,因此需要ChIP试验进行有力的支持。有研究[6]通过WB, MSP,EMSA等技术发现乳腺癌细胞的高度恶性与抑制肿瘤转移相关的TFPI-2基因启动子区过度甲基化有关,之后用ChIP试验则证实了该区域高度甲基化后确实转录水平因此受到影响,为上述的结论提供更充分的论据。类似的,Peng等人[13]用EMSA技术得出水稻转录因子OsLFL1结合于Ehd1基因的启动子区的初步结论后,采用ChIP在体内重复出了这个结果,因此最终能确定该转录因子的结合位置。

最后,ChIP是染色质结构改变,特别是组蛋白修饰后,研究全基因组活化或抑制作用的少数工具之一。ChIP可以针对乙酰化或者甲基化的组蛋白,富集该区域的DNA,因此可以进行基因组的多样性分析。2008年,Xiang等人[7]发现硒(Se)处理与前列腺癌细胞的DNA甲基化水平降低、组蛋白乙酰化水平升高、GSTP1(前列腺癌相关蛋白)活化有关。试验中,他们用ChIP技术富集了乙酰化H3-k9和甲基化H3-K9,对分离获得的DNA进行多个基因的PCR扩增。结果显示GSTP1基因在处理组和非处理组之间有显著差异,这表明Se处理的癌细胞GSTP1启动子相关的H3-K9乙酰化水平提高、H3-K3甲基化水平降低,预示Se可能具有调节染色质表观结构的功能。

正因为ChIP技术对于表观遗传学及信号转导研究是如此之重要,默克密理博特别为该领域的科学家们专门开发了的ChIP解决方案,其中完备的ChIP试剂盒免去提前准备各种试剂(包括鲑鱼精子DNA包被的琼脂糖珠子、Protein A/G等)的麻烦,专用的ChIP抗体节省了抗体测试的时间和精力,优化的protocol大大降低了ChIP实验的难度、减少摸索实验条件的时间。经过不断的改良及完善,新一代的EZ-ChIP能够提供阴性、阳性对照和DNA纯化柱,使ChIP试验更为高效可靠,大量经典文献的引用即是其品质的保证[27-29]。另外,对于应用越来越多的ChIP on CHIP,默克密理博还提供EZ-Magna ChIP试剂盒,磁珠分离技术让ChIP跨入高通量时代,为全基因组的探索插上翱翔的翅膀。

更多ChIP相关信息,请参考 密理博表观遗传学手册

关于ChIP技术问题,请参考染色质免疫沉淀(ChIP)技术的难点及应用

或致电:400-889-1988,Email联系 默克密理博生命科学市场部

或者访问 默克密理博中国博客

关于EZ ChIP产品问题,请点击此处

参考文献:

1. Zhang, Y., et al., GATA and Nkx factors synergistically regulate tissue-specific gene expression and development in vivo. Development, 2007. 134(1): p. 189-98.

2. Rossi, V., et al., A maize histone deacetylase and retinoblastoma-related protein physically interact and cooperate in repressing gene transcription. Plant Mol Biol, 2003. 51(3): p. 401-13.

3. Han, Q., et al., Gcn5- and Elp3-induced histone H3 acetylation regulate, s hsp70 gene transcription in yeast. Biochem J, 2008. 409(3): p. 779-88.

4. Grainger, D.C., et al., Genomic studies with Escherichia coli MelR protein: applications of chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarrays. J Bacteriol, 2004. 186(20): p. 6938-43.

5. Wu, C.H., et al., Combined analysis of murine and human microarrays and ChIP analysis reveals genes associated with the ability of MYC to maintain tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet, 2008. 4(6): p. e1000090.

6. Guo, H., et al., Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 was repressed by CpG hypermethylation through inhibition of KLF6 binding in highly invasive breast cancer cells. BMC Mol Biol, 2007. 8: p. 110.

7. Xiang, N., et al., Selenite reactivates silenced genes by modifying DNA methylation and histones in prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis, 2008. 29(11): p. 2175-81.

8. Sun, G., et al., Orphan nuclear receptor TLX recruits histone deacetylases to repress transcription and regulate neural stem cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(39): p. 15282-7.

9. Zhao, C., et al., A feedback regulatory loop involving microRNA-9 and nuclear receptor TLX in neural stem cell fate determination. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2009. 16(4): p. 365-71.

10. Israsena, N., et al., The presence of FGF2 signaling determines whether beta-catenin exerts effects on proliferation or neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Dev Biol, 2004. 268(1): p. 220-31.

11. Kwon, C.S., C. Chen, and D. Wagner, WUSCHEL is a primary target for transcriptional regulation by SPLAYED in dynamic control of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev, 2005. 19(8): p. 992-1003.

12. Rossi, V., et al., Maize histone deacetylase hda101 is involved in plant development, gene transcription, and sequence-specific modulation of histone modification of genes and repeats. Plant Cell, 2007. 19(4): p. 1145-62.

13. Peng, L.T., et al., Ectopic expression of OsLFL1 in rice represses Ehd1 by binding on its promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2007. 360(1): p. 251-6.

14. Omata, K., et al., Identification and characterization of the human inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase gene promoter. Apoptosis, 2008. 13(7): p. 929-37.

15. Metivier, R., et al., Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell, 2003. 115(6): p. 751-63.

16. Shi, H., et al., TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest, 2006. 116(11): p. 3015-25.

17. Tsukuda, T., et al., Chromatin remodelling at a DNA double-strand break site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature, 2005. 438(7066): p. 379-83.

18. Bernstein, B.E., et al., A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell, 2006. 125(2): p. 315-26.

19. Topp, C.N., C.X. Zhong, and R.K. Dawe, Centromere-encoded RNAs are integral components of the maize kinetochore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(45): p. 15986-91.

20. Sotelo, J., et al., Long-range enhancers on 8q24 regulate c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(7): p. 3001-5.

21. Weinmann, A.S., Novel ChIP-based strategies to uncover transcription factor target genes in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol, 2004. 4(5): p. 381-6.

22. Barski, A. and K. Zhao, Genomic location analysis by ChIP-Seq. J Cell Biochem, , 2009. 107(1): p. 11-8.

23. Kim, T.H., L.O. Barrera, and B. Ren, ChIP-chip for genome-wide analysis of protein binding in mammalian cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol, 2007. Chapter 21: p. Unit 21 13.

24. Metzger, E., et al., LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature, 2005. 437(7057): p. 436-9, .

25. Hatzis, P., et al., Genome-wide pattern of TCF7L2/TCF4 chromatin occupancy in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol, 2008. 28(8): p. 2732-44.

26. Seo, S., et al., Neurogenin and NeuroD direct transcriptional targets and their regulatory enhancers. EMBO J, 2007. 26(24): p. 5093-108.

27. Loffler, D., et al., Interleukin-6 dependent survival of multiple myeloma cells involves the Stat3-mediated induction of microRNA-21 through a highly conserved enhancer. Blood, 2007. 110(4): p. 1330-3.

28. Kim, D.H., et al., MicroRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2008. 105(42): p. 16230-5.

29. Borchert, G.M., W. Lanier, and B.L. Davidson, RNA polymerase III transcribes human microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2006. 13(12): p. 1097-101.